What Works in the Teaching of Writing?

Raising overall literacy achievement can seem daunting, but empirical research and real-life models offer a lighthouse that can guide educators. Developing self-regulation is the key.

Writing well can be taught. While teachers may hold a clear vision for how they would like their students to write, getting students to produce effective and beautiful writing independently can remain elusive. Teaching students how to self-regulate when writing dramatically lifts not just the quality of writing, but overall literacy.

Here’s how:

Don’t write a few times a week or sporadically Do write daily

Teachers must start by dedicating a daily 30- to 45-minute block to writing instruction and practice. This block should include direct instruction in strategies and mini lessons about craft, then time can be spent practicing what is learned as students write across content areas. Students can write responses to social studies and science topics. They can also write reading responses. This practical application of writing strategies should heavily emphasize the role writing can play in building knowledge, and in thinking deeply about standards such as theme or point of view.

Don’t just analyze published mentor texts Analyze peer mentor texts too

Increasing chances to write on a daily basis is a necessary key step, but not enough. We must teach, not just assign more, writing. To "teach” writing, students need to understand how to structure essays, paragraphs, and sentences. To learn this, they should see mentor texts written by peers as well as published authors, and dissect these in explicitly guided ways. Carefully reviewing peer writing on a regular basis, almost daily, is a frequently overlooked yet essential practice.

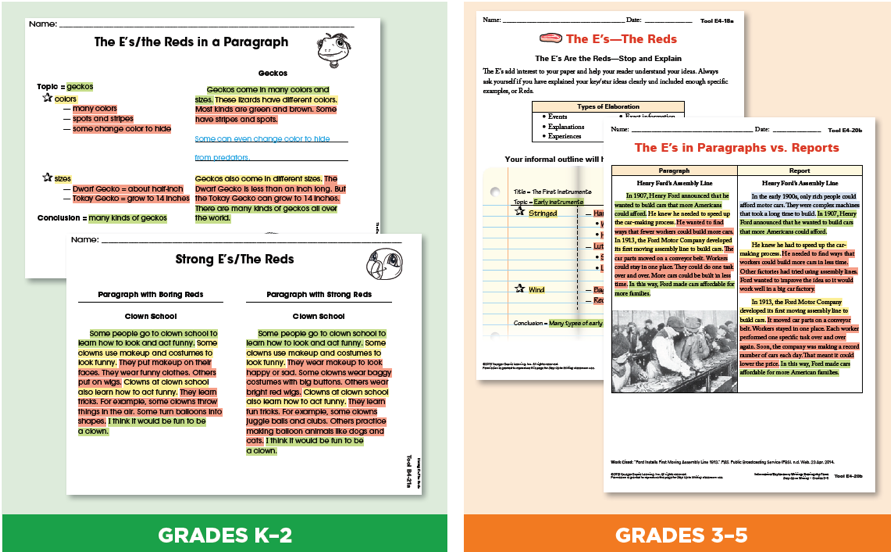

Students can review peer writing in structured ways. For example, in Step Up to Writing, writers use colors to visually see the parts in a paragraph. Then, when they start to write, they think about the different parts and are sure to include them all.

After supporting students in how to analyze the features of strong writing, our learners then need strategies to produce these themselves (Graham, 2016). One strategy might be to include the parts of TIDE when writing:

- Topic

- Information

- Details/detailed analysis

- End

This knowledge (what effective writing looks like) and how to create it (strategies) enables students to self-regulate when they write. It is also critical to start teaching text structure (TIDE) before lessons about sentences, according to the research (Graham et al, 2012). Students think in bursts of ideas, not isolated sentences. They need to organize their ideas before they can then refine sentences.

Don’t just jump in Use strategies to guide oneself when writing

Such strategies (i.e. "Include the parts of TIDE” or follow POW: Pick my ideas, Organize them, and Write) allow students to guide themselves independently. For example, after seeing a teacher or peer cognitively model writing, they can say to themselves: “The last time I wrote, my classmates told me that my argument might be stronger if I quote sources more effectively. I’ll start my organizer with a topic sentence—the T in TIDE. But now that I’m ready to think about the first piece of information (I in TIDE) to add, I’ll more carefully consider which quote will offer the most heft to my writing. I’ll look for information that is relevant and to the point.”

In these ways, instead of needing to be prompted by teachers to take next steps, students can guide themselves independently when writing. While strategies can significantly help writers, there are no short cuts. Learners still need to constantly engage deeply with academic language in complex texts and build overall knowledge to be able to write well. However, knowing how writing is structured frees students up mentally; The lower-level hurdles of how to get started and structure one’s writing can consume less conscious attention. They then have more energy to put into sentence construction and vocabulary-choice decisions writers make.

Don’t let writing block stop you Do nurture positive self-talk and identity

Next, we must also prepare our students for the affective side of writing. Writer’s block is real. Students must learn how to manage their self-talk:

- “I got this!”

- “I can do this. I’ll use my strategies.”

In fact, students can be explicitly supported in developing self-confident writer identities. This can happen as they analyze mentor texts where students see themselves reflected in what they read, as correlational studies show that students learning from culturally relevant texts outperform those who do not (Byrd, 2016). It is key to read and study great writing models that include diverse perspectives, rather than one subset of people. The texts students read, and write, should represent the many racial, gender, and cultural perspectives in our world.

Don’t just offer inviting topics, audience, and choice Do include cognitive modeling and strategies

We have all seen students catch on fire when writing about topics they chose, and when infusing their own voices. Our learners especially appreciate chances to write for real audiences and publish what they write. However, engagement is far more than just:

- Inviting topics

- Real-world audiences

- Chances to make choices

In fact, there seems to be little empirical research that these are the most key factors in lifting writing quality. Instead, cognitive modeling, developing positive self-talk, showing clear models and strategy steps for creating these are key, as well as critical formative assessment piece that may play the greatest role in raising writing achievement.

Don’t leave assessment for the end Do weave in formative assessment as a learning tool all through

Students must write a pre-assessment before writing lessons begin. This is not as much for the teacher’s benefit (It will help us plan lessons), but for the students. Our students will self-score it, and then use it to set goals, track their growth, and develop even more confidence that they can improve when they see themselves actually doing so. To teach students how to self-evaluate their growth, teachers can score one student’s writing in front of the class. This also enables teachers to "confer” with much of the class (all at once) when students share similar struggles. Students can also "confer” with one another, after they understand how to score and have frequent chances to calibrate as a group in this way.

When students understand how writing works, have strategies to guide themselves, see themselves growing, and regularly set new goals, they become motivated to want to practice writing and take risks. They become truly self-regulating and in charge of their lives as learners.

Learn additional writing strategies during Dr. Laud’s Thursday, April 23, webinar, Lift Overall Literacy through Centering Writing Instruction. Register now

Byrd, C. M. (2016). Does Culturally Relevant Teaching Work? An Examination From Student Perspectives. SAGE Open, 6(3), 215824401666074

Graham, S., Bruch, J., Fitzgerald, J., Friedrich, L., Furgeson, J., Greene, K., Kim, J., Lyskawa, J., Olson, C.B., & Smither Wulsin, C. (2016). Teaching secondary students to write effectively (NCEE 2017-4002). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Graham, S., Bollinger, A., Booth Olson, C., D’Aoust, C., MacArthur, C., McCutchen, D., & Olinghouse, N.(2012).Teaching elementary school students to be effective writers: A practice guide (NCEE 2012- 4058). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Laud, L, Patel, P., Cavanaugh, C. & Lerman, T. (2018). “Self-regulated Learning in Action” In: Connecting Self-regulated Learning and Performance with Instruction Across High School Content Areas. Springer: New York City.